Intro…

Intro…

Thanks to Kristina (Speakeasy) and Ruth (Silver Screenings) for initiating and administering the “Things I Learned from the Movies” Blog-a-thon. As in the past their “assignment” has sent me on a more introspective and autobiographical journey than I might normally attempt or share.

Please be sure to see the blogathon nightly round-ups at their websites for the wealth of interesting features this virtual gathering will surely generate. Send some comment love to the ones you really like, and consider following them.

Gimme a Second…

Stop Motion. It’s what I’ve done most of my life, from behind a camera and usually at 1/60th or 1/125th of a second. Film’s light sensitivity, as in ASA/ISO ratings, in pre-digital days offered limited choices.

Stop Motion, the animation technique, was an obsession throughout my pre to mid-teens, until the first two Led Zeppelin albums and The Who’s Live At Leeds caught my ear and I had to learn how to make that sound.

During those years I spent hours methodically clicking off one frame of film at a time through the Keystone 8mm camera my father gave me. Dad was pragmatic. It was already clear that I wasn’t going to be the fastest left handed pitcher in the history of National League Baseball, but I did share another skill set with him and that was photography and a seemingly natural understanding of visual composition.

Most of my films centered around the adventures of a clay “everyman” I called Glip. In retrospect Glip was a Gumby analog who ran around my home, raiding the refrigerator, climbing ladders, literally swinging from the chandelier. In other films Glip took on the personas of Ebenezer Scrooge, Long John Silver and Mr. Hyde, in (purportedly) comedic spins on classic literary works.

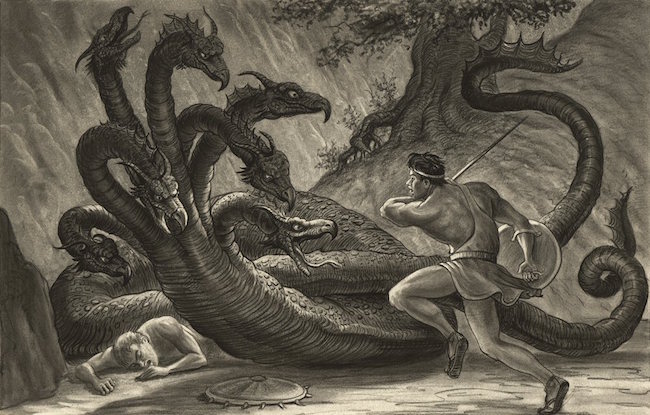

When more majestic scenarios were required my articulated 12 inch tall G.I. Joe’s became helpless subjects and were buried under plasticine to emulate my favorite fantastic film creatures. Ray Harryhausen’s mighty Cyclops was rendered – as best possible – with green clay, a faux pearl eyeball, and a toothpick horn.

Thinking In Stills…

When not producing these meisterwerks an inordinate amount of time was spent staring into a consumer grade moviola screen pouring over Castle Films’ ruthlessly edited collector’s reels. Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was my favorite. I scrubbed that film back and forth intently absorbing the specific movements applied to the Dragon versus Cyclops battle, and I was particularly obsessed with the exact frame in Jason and the Argonauts where actor Todd Armstrong drops his real sword and it is replaced by Harryhausen’s miniature blade which plunges into the heart of the seven headed hydra model.

Simultaneously I was introduced to the work of photojournalist Arthur Fellig by my Father. Fellig became popularly known as WeeGee (think Ouija board) because of his ability to divine the right spot to be in and capture the action. As my Dad pointed out, the goal is not only to produce a technically efficient photograph but to capture an image that encapsulates the event if only a single photo goes to print. In fact, with WeeGee’s rig of a 4X5 Speed Graphic camera, and single flash bulb illumination, there was no room for error. It was a “bring ‘em back alive” style of street photography and a high contrast graphic look that I began to emulate.

Looking back, these were clearly the formative seeds of my fixation with “the instant.” I watch a motion picture but recall it in primary still images. I see a still image and envision the action.

Fractions of Actions…

Eventually I came to see stop motion, the animation technique, as a misnomer. Whereas a still photographer freezes a split second of action, the animator is not stopping motion at all. The subject is static, it “moves” by virtue of a fault of human visual perception. Persistence of vision. All those incremental movements rushing by our eyes can’t be processed as single images and blur into an illusion of life. It works, from the simplest flip book to the most epic mega film.

Even so, the inverse appears to apply. As “move-y” as movies get they are still ultimately built as series of frames with some being more potent or dominant than others. Those key frames appear to be what impact on our brains when we remember a scene. I applied this perception to my animation work with a method of capturing the peak of action with additional frames, thereby boosting it’s visual imprint.

I Scream, You Scream…

Thinking in stills is not a cinematic aberration. Director Sergei Eisenstein knew it. Every film 101 student has been introduced to The Battleship Potemkin (1925) and his triptych of stone lions juxtaposed to seemingly rise to the battle call. It is a hallmark of film editing for effect called montage. Director James Whale seems to have cribbed its timing in the treble of jump cuts to close-up that underscore the first entrance of the monster in Frankenstein (1931).

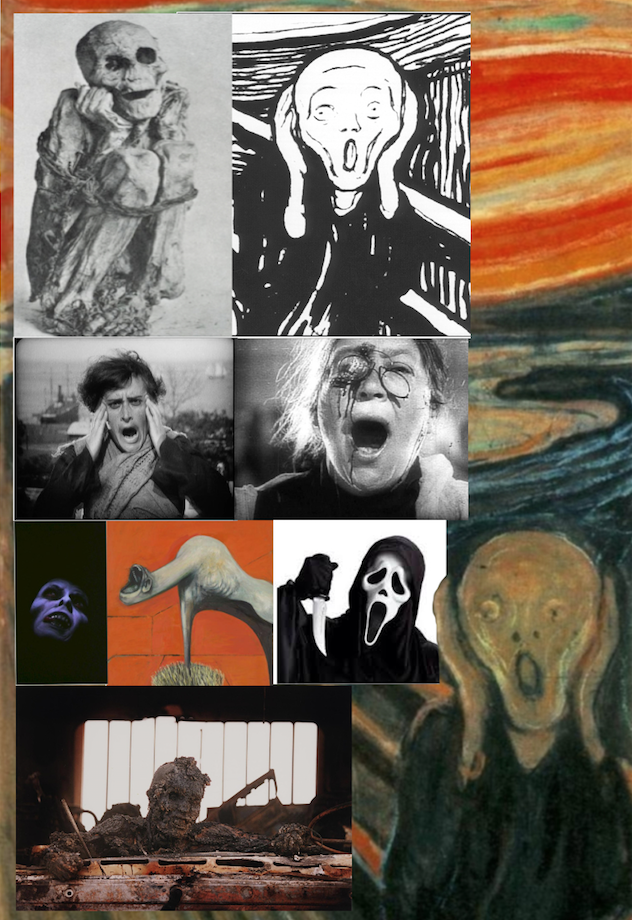

Eisenstein’s then experimental editing technique is most obvious in the famous Odessa Steps sequence. The scene is filled with examples of “stills in motion,” from the careening baby carriage to the shock and horror on the faces of the victims. Often emulated, I believe never equaled, the sequence also owes part of its origin to the iconic instant of horror portrayed by artist Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893).

Munch’s painting is one of the most familiar and widely appropriated images of this and the previous century. It represents a second in time when artist perceived “the shriek of nature” as he watched a blood red sunset over the Oslo fjord in Norway. It is a single image but it is also a movie. It contains all the information required to allow us to extrapolate a story, perceive an emotion, even if we know nothing about it before our first viewing. It conveys its peak psychological power and elicits a palpable reaction that appears to be universally, and non-verbally, understood. It’s a proto-emoji.

Instinct Karma…

Impactful visuals don’t die, they get reinterpreted. Eisenstein clearly understood the psychological power of this image and utilized it to great effect in several shots during his famed sequence. Later on, influenced by the Eisenstein scene, artist Francis Bacon rendered the screaming amorphous thing that inhabits the right section of his triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1950).

Munch’s distressing vision, one which he revisited in different media several times between 1893 and 1910, appears to tap into the collective human unconscious theorized by Professor Carl Jung. Art historian Robert Rosenbaum’s postulation that Munch may have found his initial inspiration in the gape mouthed pose of a Peruvian mummy exhibited at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris deepens the possibly of ancient archetypal connections. We only need to view the “Captain Howdy” stingers of The Exorcist series or the photo of an immolated Iraqi soldier from the first gulf war to find modern correlations.

While Eisenstein’s work presents a prime example of the frozen moment technique, other staples abound. Carl Theodor Dryer’s restriction of characters to extreme close-ups throughout The Passion of Joan of Arc reduces them to nearly static icons. There’s also Luis Bunuel’s use of freeze frames in Viridiana that transmute his beggar’s banquet tableau into an irreverent “snap shot” of Leonardo DaVinci’s The Last Supper.

Historically, freeze frames and framed friezes relate. The Roman Catholic “stations of the cross,” are essentially a 14 panel storyboard of the passion of Jesus Christ and present everything a mostly illiterate medieval congregation would have required to understand the narrative. Director Chris Marker took this concept to its filmic extreme with La Jetée, (1962). Its 28 minute runtime is composed almost entirely of black and white still images. The outcome has the feel of reading a fumetti, the pulpy “photo novellas” popular in Europe during the 1950s and 60s.

In fact, movie storyboards so closely resemble comic strips that it is no surprise that early animator Windsor McCay was also a preeminent cartoonist of his time. His Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumberland are still revered as blueprints for outsider work on the printed page. As his characters’ exploits often broke through the walls of their outlined panels, McCay also broke the “fourth wall” of the cinema screen when he toured his animated featurette Gertie the Dinosaur (1919). During the showing McCay would engage the projected cartoon creature to do his bidding, much like a trained circus elephant.

The Frame Game…

So what have I learned from the movies? Although I did not continue to pursue three dimensional animation, even as an avocation, I did take away an appreciation for the peak moment of action.

As a photojournalist I’ve aspired to catch those key moments that make images memorable. It’s not just about freezing the height of action. On candid shoots, I’ve learned to watch for the “a-ha” or eureka moments in people’s faces, the body language that reveals their personalities, and the eye contact between subjects that conveys to the viewer something special has just transpired.

Solely as a personal challenge, I often try to capture that instant by attempting to “read” the subject without resorting to rapid frame mode. It’s very hard not to succumb to the temptation of over shooting that digital photography allows. I try to honor the methods of my film days when I had to reduce an entire story to a maximum of 72 exposures. On a current photo shoot, with a DSLR and unlimited digital film resources, it appears to be anathema.

I know it’s old school, but I’m an old guy now. Utilizing the skills I’ve polished over 50 years is not just a comfort zone but offers a real sense of satisfaction. Recently I’ve been using the camera in my iPhone and Instagram, it seems the perfect platform to keep refining single image as story skills. It may even lead to doing some simple animation again.

eMotion…

Soon even the best sports and event photographers will begin to supplant their still imaging methods with 4K and 5K video captures that facilitate grabbing that peak moment from the overall action effortlessly. Does it feel like a cheat? Sure, but maybe the wheel felt like a cheat to the guy who was used to pushing a square boulder up the hill. I’m no luddite, and I look forward to working with these new technologies with the knowledge that a great image will continue to evoke authentic response no matter its creative vehicle.

SkeletonPete Says…

I had a wonderful time putting this piece but finding the flow to complete it wasn’t easy. Writing about visual communication leaves much in the synapses that (for me at least) cannot be expressed accurately with words. The thought belatedly crossed my mind to present the post as a storyboard, but deadlines (and meager skills) precluded that.

Finding Dr. Temple Grandin’s Thinking In Pictures during my research was a revelation, and an affirmation of my own previsualization techniques. I highly recommend you take a look as well.